New Yorkers with Disabilities

New York City is a melting pot with people of different cultures, religions, races and ethnicities. Adding to its diversity are more than 800,000 individuals living with disabilities, ranging from hearing and visual impairments to physical and cognitive limitations.

The ways that these artists, musicians, teachers and everyday people make sense of the city are unique and varied, but also misunderstood and often overlooked. Sense in the City documents some of New York’s most captivating disabled people as they live, work and create.

Growing Up

Bonding like family at a Korean-American home; flying like Superman at a sensory gym; and reading lessons for deaf children.

Going Out

Looking for work and looking for love; highlighting blind visual artists who make art and lead museum tours.

Home with a Mission

By Rachel Brockmann-Bryson and Elly Yu

“When a parent has a special needs child, there is a loss because of everything that child could have been,” said Edd Lee, a program director at MilAl.

Kevin and Minkyu share a room on the top floor of MilAl Mission, a group home for Korean-Americans with disabilities in Flushing, Queens. But the two are closer to brothers than roommates.

Kevin, 19, has a speech impediment that makes his language unclear, and Minkyu, 31, is the only person in the home able to translate and give Kevin a voice.

This strong sense of family is at the core of MilAl’s services. Nestled on a tree-lined street, it serves as a haven for Korean-American youth and adults with disabilities. It has three components: a group home, an after-school program and a once-a-week recreational program at a nearby church.

A Visit to the Home

Let's Play

By Shannon Ayala

“She doesn’t like to touch the sand,” said Emilia Sorrentino’s mother. “She won’t go in the sandbox. She won’t go near the sprinklers, ever.”

After school, Nick Sorrentino will fly like superman, knock down bad guys and climb a rock wall. Not bad for a six year-old with cerebral palsy and sensory processing difficulties.

In ordinary play settings, such as a park, kids like Nick or his three-year-old sister Emilia, who also has sensory sensitivities, can have fun, but they can also experience challenges. Nick gets tired fast, lacks awareness of where his body is in space, and has vision trouble, all conditions that hinder his ability to focus.

Noise and tactile sensations can overwhelm Emilia. One of the first signs that Emilia had trouble with sensory processing was her refusal to eat certain foods. She would spit out anything slimy such as pasta. “She basically eats mush and some sort of graham cracker,” her mother said.

Visual Transitions

“ASL has a whole different structure,” said Mona Greenfield about American Sign Language. “Like, ‘I want a cookie,’ is ‘Cookie me’ in sign language.”

For children who were born deaf, learning to read English is a challenge because they have never heard spoken English. Children who can hear learn how to read by translating the sounds of spoken language into written words. But deaf children communicate not through sounds but through signs and gestures. This visual language has no written version. To help deaf children learn to read, visual elements are given to spoken words.

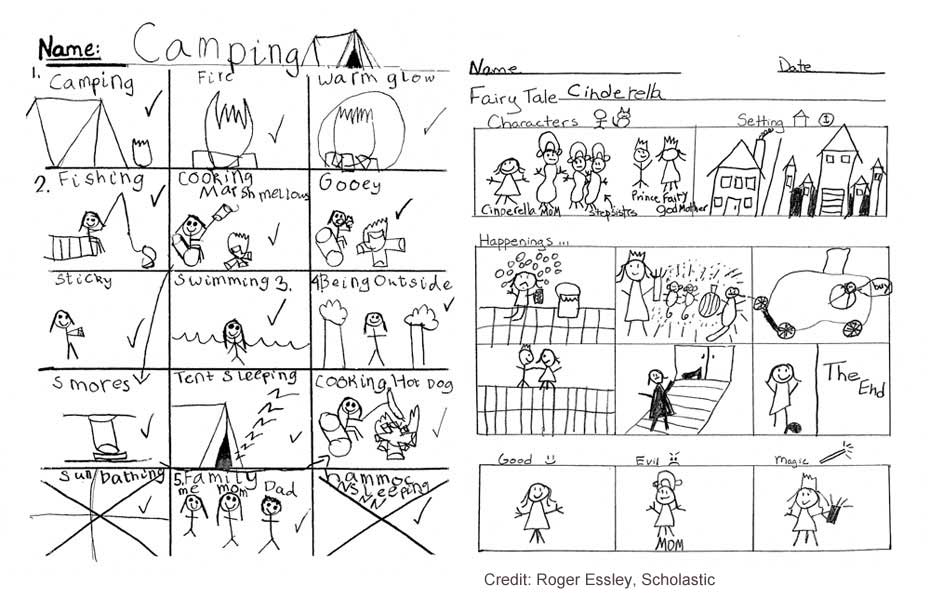

At St. Francis de Sales School for the Deaf in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, teachers have been using an unusual method to help their pupils — a method designed not for the deaf in particular, but for any child who has difficulty learning to read. Picture books, props and drawings are all part of the method, based on a book by Roger Essley called “Visual Tools.”

Deaf Cupid

By Jillian Eugenios

Kyle Kalski and Terron Moore have been together for nearly a year, and say their differences make their relationship even better – even if they do speak two different languages.

Ready, Willing and Disabled

By Catherine Featherston

“I was wearing a tie and the tie was on the rail. As far as I know – I really have no memory of how it went down – in trying to stop, the train pulled on the tie and my vertebrae got twisted around.”

It was stifling in the Bleecker Street subway station on the summer night, 17 years ago, that Brendan Costello accidentally stepped off the platform and fell into the well between the tracks. Seconds later, a train came rumbling over him. Costello, then 27, suffered damage to his first thoracic vertebrae leaving him paralyzed from his abdomen down.

For Costello, and the nearly 450,000 other working-age individuals with disabilities in New York City, getting any job – much less a personally rewarding one – can be exceptionally difficult. According to a report from the Center for Independent Living in New York, the employment rate of people with disabilities is 32 percent – substantially slower than the 73 percent employment rate of people without disabilities.

The Sound of Art

By Kathleen Caulderwood

“The thing about going to the museum experience is having the dialogue, being able to talk to other people who are sighted or low-vision and talking about the ideas behind what was going on with the piece of work.” — Busser Howell

Busser Howell lives in New York, in a post townhouse on Manhattan’s East Side. The walls are covered with his paintings — huge canvases with riots of colors, geometric designs and broad strokes. Like any other artist in New York, he regularly attends gallery openings, or museum exhibits, and even shows his own work.

But there’s one thing that makes him stand out, besides his talent. Since he was young, Busser has known that his sight wasn’t good. He had something called secondary glaucoma, a deterioration of the optic nerve, that eventually caused his blindness.

Silent Mob

By Gio Pinto

Deaf can do it

Throw your hands up the air

Deaf can do it

Throw your hands up the air

Deaf can do it

Got no fear

Deaf can do it

Except hear

Silent Mob is a deaf rap group from the Bronx, led by James Taylor aka Def Thug. The group raps in American Sign Language, but as with spoken language and traditional hip-hop and rap music, the style and lingo of deaf rappers varies.

Dolla Will, a friend of Silent Mob from Houston, signs slower and with Houston slang. Def Jef throws his signs fast, on par with the lyrical speed of the rapper Twista.

Members of the group formed Silent Mob in high school, when they attended the Lexington School for the Deaf. The groups’ songs often contain themes of what it means to be deaf, such as communicating via text message and “deaf can do it.”

The Art of the Lone Man

By Tanisia Morris

When Queens-based painter Ralph Mindicino lost his right leg to bone cancer at the age of 14, his life changed drastically. He felt alienated from friends and he struggled to navigate the city. Mindicino, 53, found solace in art, a passion that he developed as a child.

A graduate of the State University of New York at Fredonia and at Stony Brook, Mindicino has worked in bronze and steel sculpture, pottery and oil painting. Over the last decade he has worked exclusively with acrylic plexiglass to create abstract and figurative works that are rich in color and explore the theme of the lone man. The series features an isolated character with color-drenched cityscapes.

In this interview, he talks about how his experience living with a disability has inspired his art. He describes the challenges of creating works on plexiglass and how the meticulous engraving process has helped to distract him from the day-to-day struggles as an amputee.

Blind On Stage

By Tara Bracco

Pamela Sabaugh, an actress who has juvenile macular degeneration, began studying theater in Detroit and has been acting professionally in New York since 1997. Sabaugh is legally blind with only peripheral vision. Most recently, Sabaugh performed in the play “According to Goldman,” by Bruce Graham, produced by Theater Breaking Through Barriers.

Staging Untold Stories

By Tara Bracco

Gregg Mozgala, an actor with cerebral palsy, talks about theater’s ability to break down barriers and explains why he founded The Apothetae, a theater company dedicated to creating full-length plays about the experiences of people with disabilities. The company’s first production – “The Penalty,” by Clay McLeod Chapman, with music by Robert M. Johanson – begins June 14th at Dixon Place on the Lower East Side.

Musical Muse

By Tanisia Morris

New York-based singer-songwriter Lachi is legally blind and describes her condition as severely nearsighted. Originally from Raleigh, North Carolina, she says that her disability is the driving force behind her music, which is a mix of pop, indie rock and alternative.

Lachi released her debut, self-titled album in 2010. Since then, her music has been featured in a host of television shows, documentaries and radio programs, including Oprah Radio, CBS Radio and NME.

She has performed at venues and festivals such as Joe’s Pub, the Knitting Factory, CMJ, SXSW and New York University, where she received her Master’s degree in music technology. Her sophomore album, “Make Some Noise,” will be released later this year.